Have you ever wondered where the diamonds in your engagement ring or earrings started life? You may have bought your ring from an Edinburgh jeweller, or from Clare Blatherwick FGA DGA, but those diamonds began their journey thousands of years ago deep underground before being cut and polished and set into a piece of jewellery. And the first time a human being will have set eyes on those diamonds will likely be in a diamond mine. I was lucky enough to visit the Cullinan diamond mine in South Africa recently to see that stage a diamond's journey. Oh, and on arrival I was told that if you find a diamond while you are visiting the mine, the mine owners will buy it from you, so it pays to keep your eyes peeled.

Only a short distance from Pretoria, when it was established in 1902 the Cullinan mine was initially known as The Premier Mine. It has produced some of the world’s most famous diamonds, including The Cullinan which was named after the founder of the mine, Thomas Cullinan, and whilst in its rough state, weighed 3106 carats. Two of the diamonds cut from the Cullinan diamond crystal are now part of the British Crown Jewels and are known as The Great Star of Africa which is in the Sovereign’s Sceptre and The Lesser Star of Africa which is in the Imperial State Crown.

What really sets this mine apart from others though, is its greater than average production of exceptionally rare (and exceptionally valuable) blue diamonds. My blog post ‘Diamonds are white…aren’t they?’ looks at the exciting world of coloured diamonds.

The mine is owned now by the Petra mining company.

Diamonds are usually formed in vertical 'pipes' of the rock Kimberlite. These carrot shaped pipes are thought to originate in the Earth’s mantle, forcing their way up to the crust and bringing diamonds with them. Kimberlite is a pretty unexciting looking rock but hides something much more interesting and desirable!

From the surface, evidence of the pipe can be seen with a 32-hectare hole which will get deeper as the mining operations continue and the pipe is block caved in the hunt for diamonds. The scale is truly enormous. I was unable to fit it into one photograph despite being some considerable distance away. The large structures to the left side of the hole are some of the historic mine buildings, and modern day surface operations can be seen to the right.

The surface operations were vast, and extremely muddy. Kimberlite becomes a thick sticky mud when it is processed in the hunt for diamond crystals. Enormous piles of kimberlite rock passing through processing buildings and along moving conveyor belts were in evidence.

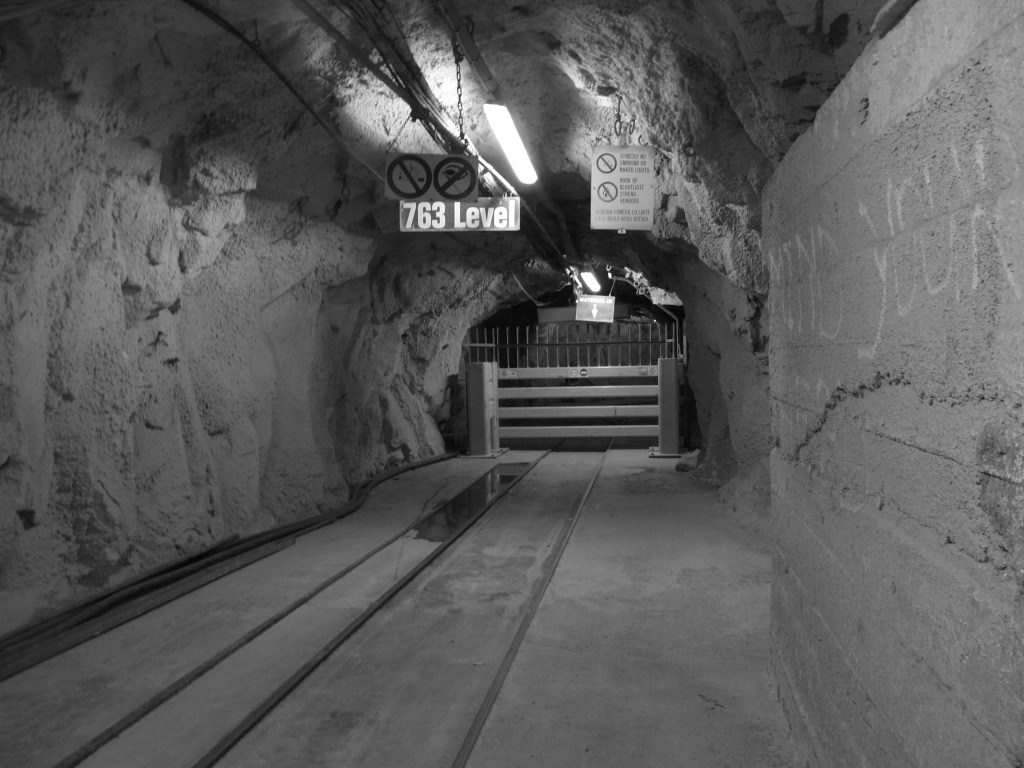

After being kitted out with safety apparatus and heading past warning signs about blast times, I shared a long lift journey with some miners who were starting their shift. We descended 763 metres underground and entered, to me, a very alien place, far removed from the world of a Bond Street jeweller or auctioneer.

The entrance to the 763 level was cold and windy – principally to do with the structure of the mine, but it was a relief to feel fresh air – I had wrongly assumed it would be stiflingly hot.

I was shown around by a retired mine shift manager who explained what day to day life was like for the mine workers, especially the importance of strong camaraderie and friendship between them. As we walked through the tunnels, enormous machines thundered past us throwing up fine dust and thick grey mud.

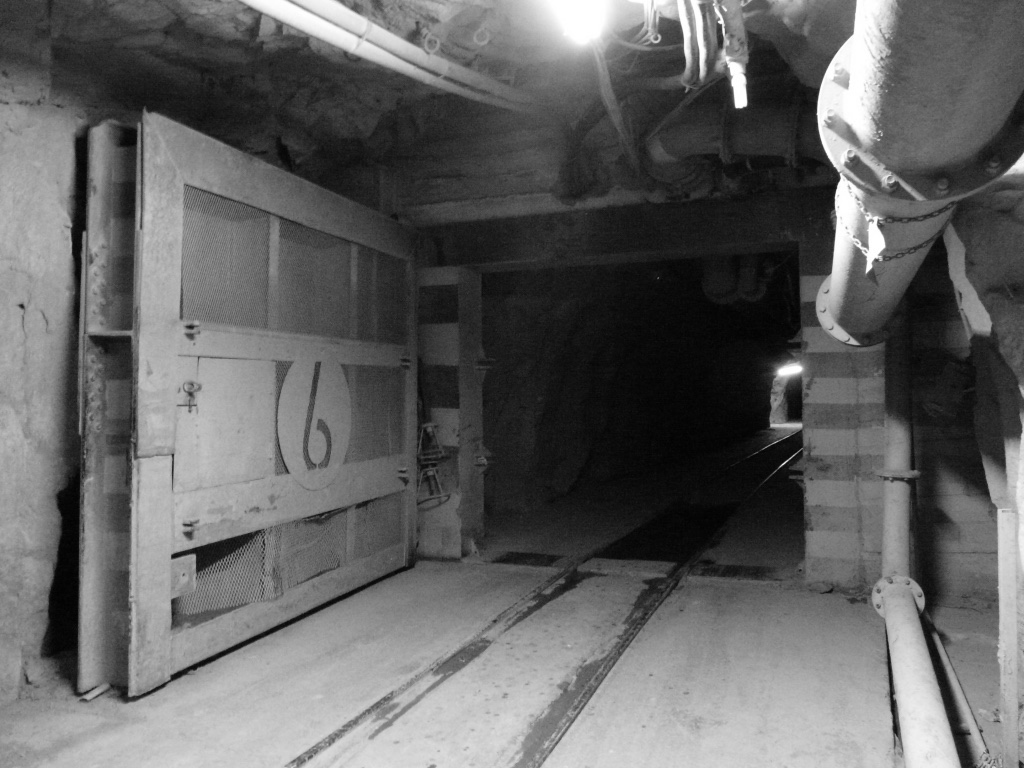

We walked through very long tunnels, following the tracks used by the rail trucks which carry kimberlite to processing areas.

The tunnels are interrupted at various points by thick metal safety doors to seal off sections of the mine if there is an incident such as a flood.

The underground operations areas were enormous, huge cathedral-like caves with garages, mechanics bays, staff canteens and offices. Like an underground town, but thick with mud on the ground and dust in the air (how is this combination possible?).

.jpg)

The huge drilling machines that burrow their extending arms deep into the sides of the kimberlite pipe and allow explosives to be inserted as part of the block caving mining process were impressive in their scale.

The vehicles moving around the mine have been adapted to navigate through the thick mud.

There are areas where the initial processing of the blasted kimberlite takes place. The rock is moved by trains or along thundering conveyor belts and then tipped through grates to sort by size for further processing before heading above ground.

After a slow journey back to the surface, I was shown the mine ‘tailings’. This is kimberlite which has been processed and thought to be clear of all diamonds. But, like many things, time sees improvement in technique and some of these tailings piles have been untouched since the early part of the 20th century and are being reprocessed now with some considerable success. According to my guide, blue diamonds are being found in good numbers here, having been missed or even dismissed as glass first time round. With the world record auction price for a fancy vivid blue diamond currently standing at just over $4million per carat, it certainly seems worth having a second look.

Overall, the scale was breathtaking. But at only 2.25cts of rough diamond crystals per tonne of rock being found here, the scale does need to be enormous.

So, when you want to buy those diamond earrings you have always dreamed of, let’s spare a moment to think about what a truly amazing journey they have been on.

Contact Clare to discuss the stage of the diamond's journey that sees it arrive in your collection.